Slovenia

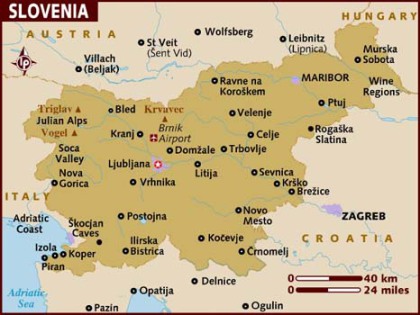

Slovenia (Slovene: Slovenija), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Republika Slovenija), is the most westernly positioned and the richest Slavic nation state. It is situated in South-Central Europe, at the crossroad of main European cultural and trade routes. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Croatia to the south and southeast, and Hungary to the northeast. It covers 20,273 square kilometers (7,827 sq. mi) and has a population of 2.05 million.

Slovenia is a bicameral parliamentary republic, member of the European Union, the Eurozone, the Schengen area, NATO, and OECD. Relative to its geography, history, economy, culture, and language, it is a very diverse country distinguished by a transitional character. Its capital and largest city is Ljubljana.

The national flag of Slovenia features three equal horizontal bands of white (top), blue, and red, with the Slovenian coat of arms located in the upper hoist side of the flag centered in the white and blue bands. The coat of arms is a shield with the image of Mount Triglav, Slovenia's highest peak, in white against a blue background at the center; beneath it are two wavy blue lines representing the Adriatic Sea and local rivers, and above it are three six-pointed golden stars arranged in an inverted triangle which are taken from the coat of arms of the Counts of Celje, the great Slovenian dynastic house of the late 14th and early 15th centuries.

The flag's colors are considered to be Pan-Slavic, but they actually come from the medieval coat of arms of the Duchy of Carniola, consisting of a blue eagle on a white background with a red-and-gold crescent. The existing Slovene tricolor was raised for the first time in history during the Revolution of 1848 by the Slovene Romantic nationalist activist and poet Lovro Toman on April 7, 1848, in Ljubljana, in response to a German flag which was raised on top of Ljubljana Castle.

Slovenian Flag and Coat of Arms

Historically, the current territory of Slovenia was part of many different state formations, including the Roman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire, followed by the Habsburg Monarchy. In 1918, the Slovenes exercised self-determination for the first time by co-founding the internationally unrecognized State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, which merged into Yugoslavia. During World War II, Slovenia was occupied and annexed by Germany, Italy, and Hungary only to emerge afterwards as a founding member of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In 1991, after the introduction of multi-party representative democracy, Slovenia declared independence from Yugoslavia. In 2004, it entered NATO and the European Union, and in 2007 it was the first former Communist country to join the Eurozone.

The territory of Slovenia is mainly hilly or mountainous and characterized by exceptionally high landscape and biological diversity and a mosaic structure, which are a result of natural attributes and the long-lasting presence of humans. Four major European geographic units interweave here: the Alps, the Dinaric Alps, the Mediterranean, with a small portion of coastline along the Adriatic Sea, and the Pannonian Plain. The climate is temperate and significantly influenced by the variety of territory, with a strong interaction of the continental climate, the sub-Mediterranean climate and Alpine climate across most of the country. The country is one of the water-richest in Europe, with a dense river network, a rich aquifer system, and significant karstic underground watercourses. Over half of the territory is covered by forest.

Lake Bled, one of the most popular tourist destinations in Slovenia

The settlement of Slovenia is dispersed and uneven. The Slavic, Germanic, Romance and Uralic linguistic and cultural groups have been meeting here. The dominant population is Slovene, but it has almost never been homogenous. Slovene is the only official language throughout the country, whereas Italian and Hungarian are regional minority languages.

Roman Catholicism as well as Lutheranism have markedly influenced the formation of the Slovenian culture and identity. Nowadays, Slovenia is a largely secularized country.

The economy of Slovenia is small, open, export-oriented and subsequently, heavily influenced by international circumstances. With its diversity of landscapes, Slovenia is a natural sports venue, with many Slovenians actively practicing sport and reaching top successes particularly in winter sports, water sports, mountaineering, and endurance sports.

There are numerous types of traditional costumes in different parts of Slovenia, but in the 19th century the Alpine type was chosen to represent the traditional clothes.

Administrative Divisions

Officially, Slovenia is subdivided into 211 municipalities (eleven of which have the status of urban municipalities). The municipalities are the only body of local autonomy in Slovenia. Besides, there also exist 62 administrative districts, officially called "Administrative Units" (upravne enote), which are not a body of local self-government, but territorial sub-units of government administration. The Administrative Units are named after their capital, and are headed by a Head of the Unit (načelnik upravne enote), appointed by the Minister of Public Administration.

Each municipality is headed by a Mayor (župan), elected every 4 years by popular vote, and a Municipal Council (občinski svet). In the majority of the municipalities, the municipal council is elected through the system of proportional representation; only few smaller municipalities use the plurality voting system. In the urban municipalities, the municipal councils are called Town (or City) Councils. Every municipality also has a Head of the Municipal Administration (načelnik občinske uprave), appointed by the Mayor, who is responsible for the functioning of the local administration.

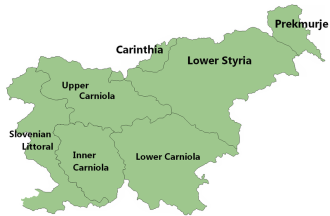

However, regional identity is strong in Slovenia. The traditional regions of Slovenia, based on the former four Habsburg crown lands (Carniola, Carinthia, Styria, and the Littoral) are the following:

| English Name | Native Name | Largest Town |

| Slovenian Littoral | Primorska | Koper/Capodistria |

| Upper Carniola | Gorenjska | Kranj |

| Inner Carniola | Notranjska | Postojna |

| Lower Carniola | Dolenjska | Novo Mesto |

| Carinthia | Koroška | Ravne na Koroškem |

| Lower Styria | Štajerska | Maribor |

| Prekmurje | Prekmurje | Murska Sobota |

Ljubljana was historically the administrative center of Carniola. However, from the mid-19th century onward, it has not been considered part of any of the three subdivisions of Carniola (Upper, Lower and Inner Carniola). Nowadays, it is not considered part of any of the traditional historical regions of Slovenia.

For statistical reasons, Slovenia is also subdivided into 12 statistical regions, which have no administrative function. These are further subdivided into two macroregions for the purpose of the Regional policy of the European Union. These two macroregions are:

- East Slovenia (Vzhodna Slovenija – SI01), which groups the regions of Pomurska, Podravska, Koroška, Savinjska, Zasavska, Spodnjeposavska, Jugovzhodna Slovenija and Notranjsko-kraška.

- West Slovenia (Zahodna Slovenija – SI02), which groups the regions of Osrednjeslovenska, Gorenjska, Goriška and Obalno-kraška.

Ljubljana is the capital and largest city of Slovenia. Population (2012): 272,140.

Prehistory

Present-day Slovenia has been inhabited since prehistoric times, and there is evidence of human habitation from around 250,000 years ago. A pierced cave bear bone, dating from 43100 ± 700 BP, found in 1995 in Divje Babe cave near Cerkno, is possibly the oldest musical instrument discovered in the world. In the 1920s and 1930s, artifacts belonging to the Cro-Magnon such as pierced bones, bone points, and needle were found by archaeologist Srečko Brodar in Potok Cave.

In 2002, remains of pile dwellings over 4,500 years old were discovered in the Ljubljana Marshes, now protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the Ljubljana Marshes Wooden Wheel, the oldest wooden wheel in the world. It shows that wooden wheels appeared almost simultaneously in Mesopotamia and Europe. In the transition period between the Bronze age to the Iron age, the Urnfield culture flourished. Archaeological remains dating from the Hallstatt period have been found, particularly in southeastern Slovenia, among them a number of situlas in Novo Mesto, the "Town of Situlas". In the Iron Age, present-day Slovenia was inhabited by Illyrian and Celtic tribes until the 1st century BC.

The Vače Situla, dating from the 5th century BC, found in Vače, Slovenia

Ancient Romans

When the Ancient Romans conquered the area, they established the provinces of Pannonia, and Noricum and present-day western Slovenia was included directly under Roman Italia as part of the X region Venetia et Histria. The Romans established posts at Emona (Ljubljana), Poetovio (Ptuj), and Celeia (Celje); and constructed trade and military roads that ran across Slovene territory from Italy to Pannonia.

The Orpheus Monument, Ptuj, Slovenia

The Orpheus Monument (slov. Orfejev spomenik) is a Roman monument in Ptuj (lat. Poetovium) - Slovenia’s oldest city. It is located at Slovene Square, the town's central square, in front of the Town Tower. It is the oldest public monument preserved in its original location in Slovenia, the largest discovered monument from the Roman province of the Pannonia Superior, and the symbol of Ptuj. The monolith was originally a grave marker, erected in the 2nd century AD to honor the memory of Marcus Valerius Verus, the duumvir (mayor) of Roman Poetovio. In the Middle Ages, it was used as a pillory. Criminals were tied to the iron rings attached to its lower part. Since March 2008, it has the status of a national cultural monument.

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the area was subject to invasions by the Huns and Germanic tribes during their incursions into Italy. A part of the inner state was protected with a defensive line of towers and walls called Claustra Alpium Iuliarum. A crucial battle (the Battle of the Frigidus) between Theodosius I and Eugenius took place in the Vipava Valley in 394.

The Battle of the Frigidus, also called the Battle of the Frigid River, was fought between 5-6 September 394, between the army of the Eastern Emperor Theodosius I and the army of Western Roman ruler Eugenius. Because the Western Emperor Eugenius (though nominally Christian) had pagan sympathies, the war assumed religious overtones, with Christianity pitted against the last attempt at a pagan revival. The battle was the last serious attempt to contest the Christianization of the empire; its outcome decided the outcome of Christianity in the western Empire, and the final decline of Greco-Roman polytheism in favor of Christianity over the following century.

Battle of the Frigidus by Janez Vajkard Valvasor (1689)

Slavic Settlement

The Slavic tribes migrated to the Alpine area after the westward departure of the Lombards (the last Germanic tribe) in 568, and with aid from Avars established a Slavic settlement in the Eastern Alps. From 623 to 624 or possibly 626 onwards, King Samo (Latin: Samon) united the Alpine, Western, and Northern Slavs against the nomadic Eurasian Avars and established what is referred to as Samo's Kingdom. After its disintegration following Samo's death in 658 or 659, the ancestors of Slovenes located in present-day Carinthia formed the independent duchy of Carantania. Other parts of present-day Slovenia were again ruled by Avars before Charlemagne's victory over them in 803.

King Samo, reign: 623-658

The Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period

In the mid-8th century, Carantania became a vassal duchy under the rule of the Bavarians, who began spreading Christianity. Three decades later, the Carantanians were incorporated, together with the Bavarians, into the Carolingian Empire. During the same period Carniola, too, came under the Franks, and was Christianized from Aquileia. Following the anti-Frankish rebellion of Ljudevit Posavski at the beginning of the 9th century, the Franks removed the Carantanian princes, replacing them with their own border dukes. Consequently, the Frankish feudal system reached the Slovene territory.

The Magyar invasion of the Pannonian Plain in the late 9th century effectively isolated the Slovene-inhabited territory from the western Slavs. Thus, the Slavs of Carantania and of Carniola began developing into an independent Slovene ethnic group. After the victory of Emperor Otto I over the Magyars in 955, Slovene territory was divided into a number of border regions of the Holy Roman Empire. Carantania, being the most important, was elevated into the Duchy of Carinthia in 976.

A depiction of an ancient democratic ritual of Slovene-speaking tribes, which took place on the Prince's Stone in Slovene language until 1414

In the late Middle Ages, the historic provinces of Carniola, Styria, Carinthia, Gorizia, Trieste, and Istria developed from the border regions and were incorporated into the medieval German state. The consolidation and formation of these historical lands took place in a long period between the 11th and 14th centuries, and were led by a number of important feudal families, such as the Dukes of Spannheim, the Counts of Gorizia, the Counts of Celje, and, finally, the House of Habsburg. In a parallel process, an intensive German colonization significantly diminished the extent of Slovene-speaking areas. By the 15th century, the Slovene ethnic territory was reduced to its present size.

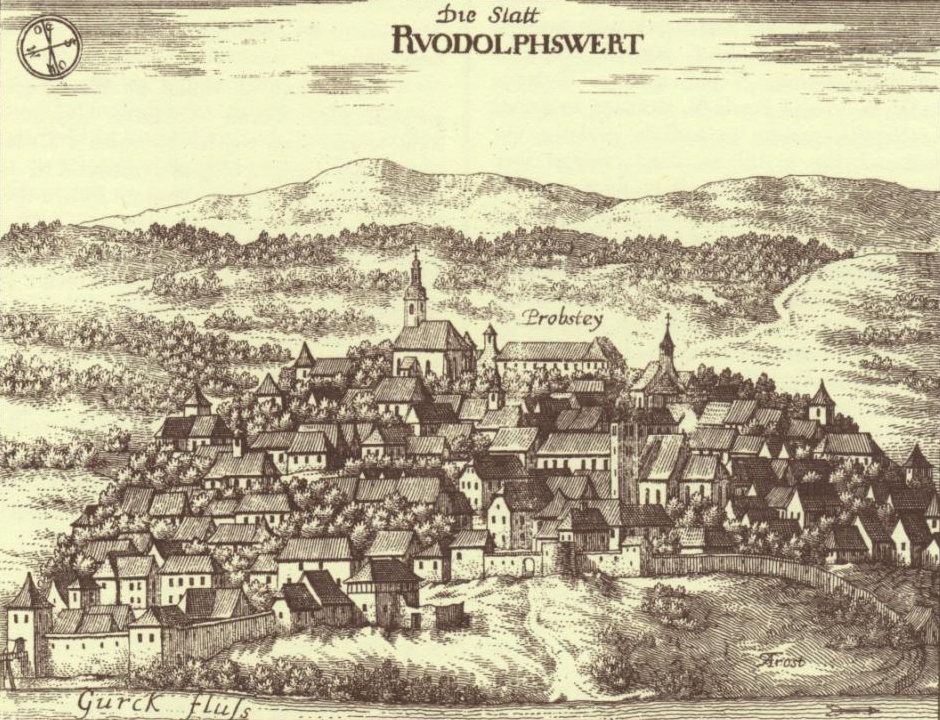

Novo Mesto was founded by the Habsburg archduke Rudolf IV of Austria in 1365

Novo Mesto (literally "New Town"), Slovenia has been settled since pre-history. The town itself was founded by the Habsburg archduke Rudolf IV of Austria on April 7, 1365 as Rudolfswerth. The Austrian Habsburgs received the Carniolan March from the hands of Emperor Louis IV in 1335 and in 1364 Rudolf "the Founder" proclaimed himself a Duke of Carniola. The name Neustadt was given in the early 15th century. Following World War I and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the city passed to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and was officially renamed Novo Mesto.

In the 14th century, most of the territory of Slovenia was taken over by the Habsburgs. The counts of Celje, a feudal family from this area who in 1436 acquired the title of state princes, were their powerful competitors for some time. This large dynasty, important at a European political level, had its seat in Slovene territory but died out in 1456. Its numerous large estates subsequently became the property of the Habsburgs, who retained control of the area right up until the beginning of the 20th century.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the Slovene Lands suffered a serious economic and demographic setback because of the Turkish raids. In 1515, a peasant revolt spread across nearly the whole Slovene territory. In 1572 and 1573 the Croatian-Slovenian peasant revolt wrought havoc throughout the wider region. Such uprisings, which often met with bloody defeats, continued throughout the 17th century.

The Ottoman army battling the Habsburgs in Slovenia during the Great Turkish War

Between the 18th Century and the End of World War I

The Slovene Lands were part of the Illyrian provinces, the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary. Slovenes inhabited most of Carniola, the southern part of the duchies of Carinthia and Styria, the northern and eastern areas of the Austrian Littoral, as well as Prekmurje in the Kingdom of Hungary. Industrialization was accompanied by construction of railroads to link cities and markets, but the urbanization was limited.

Due to limited opportunities, between 1880-1910 there was extensive emigration, and around 300,000 Slovenes (i.e. 1 in 6) emigrated to other countries, mostly to the US, but also to South America (main part to Argentina), Germany, Egypt, and to larger cities in Austria-Hungary, especially Zagreb and Vienna. The locations in the United States where many Slovenians settled were areas with substantial industrial and mining activities: Pittsburgh, Chicago, Pueblo, Butte, and the Salt Lake Valley. The men were important as workers in the mining industry, because of some of the skills they brought from Slovenia. The area of the United States with the highest concentration of Slovenian immigrants is Cleveland, Ohio. Despite this, the Slovene population increased significantly. Literacy was exceptionally high, at 80-90%.

Slovenians in Haughville, Indianapolis, USA, April 11, 1923

The 19th century also saw a revival of culture in the Slovene language, accompanied by a Romantic nationalist quest for cultural and political autonomy. The idea of a United Slovenia, first advanced during the revolutions of 1848, became the common platform of most Slovenian parties and political movements in Austria-Hungary. During the same period, Yugoslavism, an ideology stressing the unity of all South Slavic peoples, spread as a reaction to Pan-German nationalism and Italian irredentism.

World War I

World War I brought heavy casualties for the Slovenes, particularly the twelve Battles of the Isonzo, which took place in present-day Slovenia's western border area. Ernest Hemingway's "A Farewell to Arms" is partly set in the events along this front.

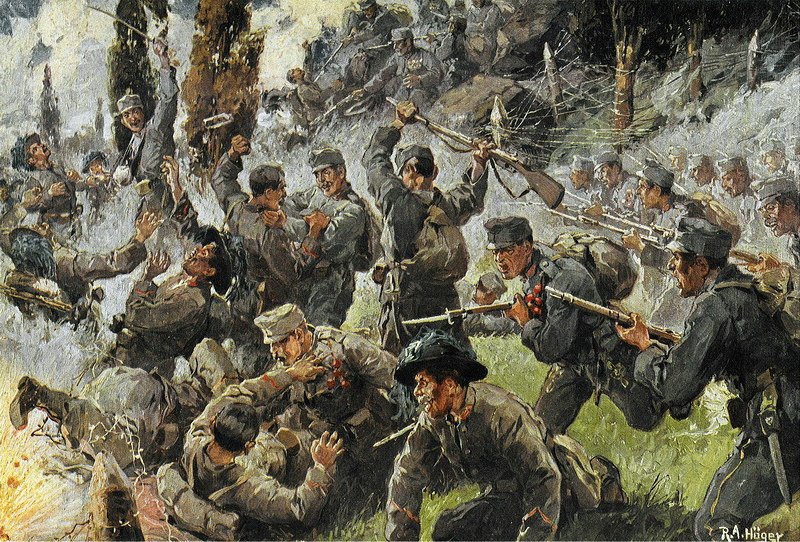

The Battles of the Isonzo (known as the Isonzo Front by historians, and "Soška fronta" by the territory's mainly Slovene population) were a series of twelve battles between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian armies in World War I mostly on the territory of present-day Slovenia, and the remainder in Italy along the Isonzo (Soča) River on the eastern sector of the Italian Front between June 1915 and November 1917.

Depiction of the Battle of Doberdò (slov. Doberdob), August 6, 1916

The Battle of Doberdò was one of the bloodiest battlefields of World War I, fought in August 1916 between the Italian and Austro-Hungarian Armies, composed mostly of Hungarian and Slovenian regiments.

Austro-Hungarian supply line over the Vršič pass, Slovenia, October 1917

Hundreds of thousands of Slovene conscripts were drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army, and over 30,000 of them died. Hundreds of thousands of Slovenes from Gorizia and Gradisca were resettled in refugee camps in Italy and Austria. While the refugees in Austria received decent treatment, the Slovene refugees in Italian camps were treated as state enemies, and several thousand died of malnutrition and diseases between 1915 and 1918. Entire areas of the Slovene Littoral were destroyed.

Remains of Kluže, an Austro-Hungarian fortification near Bovec, Slovenia

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Slovene People's Party launched a movement for self-determination, demanding the creation of a semi-independent South Slavic state under Habsburg rule. The proposal was picked up by most Slovene parties, and a mass mobilization of Slovene civil society, known as the Declaration Movement, followed. This demand was rejected by the Austrian political elites; but following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the aftermath of the First World War, the National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs took power in Zagreb on October 6, 1918. On October 29, independence was declared by a national gathering in Ljubljana, and by the Croatian parliament, declaring the establishment of the new State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.

The proclamation of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs at Congress Square in Ljubljana on October 20, 1918

On December 1, 1918 the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs merged with Serbia, becoming part of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes; in 1929 it was renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The main territory of Slovenia, being the most industrialized and westernized compared to other less developed parts of Yugoslavia, became the main center of industrial production: Compared to Serbia, for example, Slovenian industrial production was four times greater; and it was 22 times greater than in Macedonia. The interwar period brought further industrialization in Slovenia, with rapid economic growth in the 1920s, followed by a relatively successful economic adjustment to the 1929 economic crisis and Great Depression.

Following a plebiscite in October 1920, the Slovene-speaking southern Carinthia was ceded to Austria. With the Treaty of Trianon, on the other hand, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was awarded the Slovene-inhabited Prekmurje region, formerly part of Austro-Hungary.

Slovenes living in territories that fell under the rule of the neighboring states: Italy, Austria and Hungary, were subjected to assimilation.

Fascist Italianization of the Slovene Littoral and Resistance

The Treaty of Rapallo of 1920 left approximately 327,000 out of the total population of 1.3 million Slovenes in Italy. After the fascists took over the power in Italy, they were subjected to a policy of violent Fascist Italianization. This caused a mass emigration of Slovenes, especially the middle class, from the Slovenian Littoral and Trieste to Yugoslavia and South America. Those who remained organized several connected networks of both passive and armed resistance. The most famous was the militant anti-fascist organization TIGR, formed in 1927 in order to fight Fascist oppression of the Slovene and Croat populations in the Julian March.

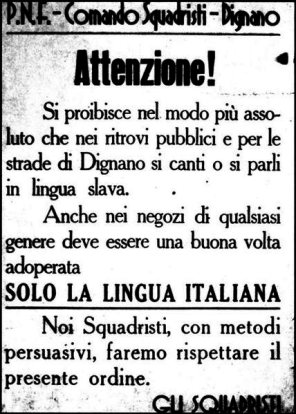

A leaflet from the period of Fascist Italianization

A leaflet from the period of Fascist Italianization prohibiting singing or speaking in the "Slavic language" in the streets and public places of Vodnjan. Signed by the Squadristi (blackshirts), and threatening the use of "persuasive methods" in enforcement. Squadrismo consisted of fascist squads who were led by the Ras from 1918-1924. As a movement it grew from the inspiration many Ras leaders found from Mussolini, but was not directly controlled by Benito Mussolini.

Slovenia During and After World War II

Slovenia was the only present-day European nation that was trisected and completely annexed into both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy during WW II. In addition, the Prekmurje region in the east was annexed to Hungary, and some villages in the Lower Sava Valley were incorporated in the newly created Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia.

The axis forces invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941 and defeated the country in a few weeks. The southern part, including Ljubljana, was annexed to Italy, while the Nazis took over the northern and eastern parts of the country. The Nazis had a plan of ethnic cleansing of these areas, and they resettled or expelled the local Slovene civilian population to the puppet states of Nedić's Serbia (7,500) and NDH (10,000). In addition, some 46,000 Slovenes were expelled to Germany, including children who were separated from their parents and allocated to German families. At the same time, the ethnic Germans in the Gottschee enclave in the Italian annexation zone were resettled to the Nazi-controlled areas cleansed of their Slovene population. Around 30,000 to 40,000 Slovene men were drafted to the German Army and sent to Eastern front. Slovene language was banned from education, and its use in the public life was limited to the absolute minimum.

Adolf Hitler on the Old Bridge in Maribor in 1941

In south-central Slovenia, annexed by Fascist Italy and renamed to Province of Ljubljana, the Slovenian National Liberation Front was organized in April 1941. Led by the Communist Party, it formed the Slovene Partisan units as part of the Yugoslav Partisans led by the Communist leader Josip Broz Tito.

Tito and the partisan supreme command during World War II in Yugoslavia, May 1944

After the resistance started in summer 1941, Italian violence against the Slovene civilian population escalated, as well. The Italian authorities deported some 25,000 people to the concentration camps, which equaled 7.5% of the population of their occupation zone. The most infamous ones were Rab and Gonars. To counter the Communist-led insurgence, the Italians sponsored local anti-guerilla units, formed mostly by the local conservative Catholic Slovene population that resented the revolutionary violence of the partisans. After the Italian armistice of September 1943, the Germans took over both the Province of Ljubljana and the Slovenian Littoral, incorporating them into what was known as the Operation Zone of Adriatic Coastal Region. They united the Slovene anti-Communist counter-insurgence into the Slovene Home Guard and appointed a puppet regime in the Province of Ljubljana. The anti-Nazi resistance however expanded, creating its own administrative structures as the basis for Slovene statehood within a new, federal and socialist Yugoslavia.

Headstone at the graves of Gorenje Polje residents killed by the Nazis in 1945

In 1945, Yugoslavia was liberated by the partisan resistance and soon became a socialist federation known as the People's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Slovenia joined the federation as a constituent republic, led by its own pro-Communist leadership.

Approximately 8% of the entire Slovene population died during WWII (the overall number of WWII casualties in Slovenia is estimated at 97,000). The small Jewish community, mostly settled in the Prekmurje region, perished in 1944 in the holocaust of Hungarian Jews. The German speaking minority, amounting to 2.5% of the Slovenian population prior to WWII, was either expelled or killed in the aftermath of the war. Thousands of Istrian Italians were killed in the foibe massacres, and more than 25,000 fled or were expelled from Slovenian Istria in the aftermath of the war.

The Socialist Period

Following the re-establishment of Yugoslavia during World War II, Slovenia became part of Federal Yugoslavia. A socialist state was established, but because of the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, economic and personal freedoms were broader than in the rest of the Eastern Bloc. In 1947, the Slovene Littoral and the western half of Inner Carniola, which had been annexed by Italy after the World War One, were annexed to Slovenia.

After the failure of forced collectivization that was attempted from 1949-53, a policy of gradual economic liberalization, known as workers self-management, was introduced under the advice and supervision of the Slovene Marxist theoretician and Communist leader Edvard Kardelj, the main ideologue of the Titoist path to socialism. Suspected opponents of this policy both from within and outside the Communist party were persecuted and thousands were sent to the Goli otok gulag.

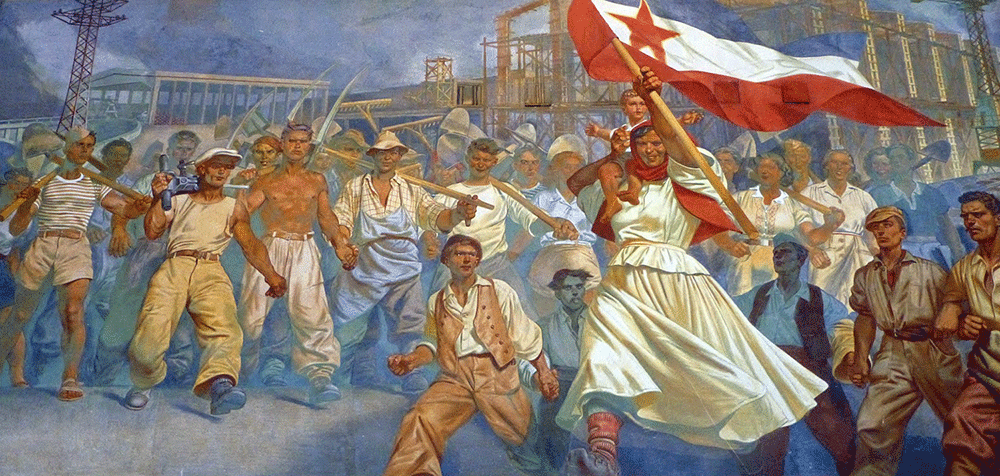

Part of the wall mural at Tito’s "Vila Bled", Bled, Slovenia

The late 1950s saw a policy of liberalization in the cultural sphere, as well, and border crossing into neighboring Italy and Austria was allowed again, under limited restriction. Until the 1980s, the Slovenia enjoyed relatively broad autonomy within the federation. In 1956, Josip Broz Tito, together with other leaders, founded the Non-Aligned Movement. Particularly in the 1950s, Slovenia's economy developed rapidly and was strongly industrialized. With further economic decentralization of Yugoslavia in 1965-66, Slovenia's domestic product was 2.5 times the average of Yugoslav republics.

Opposition to the regime was mostly limited to intellectual and literary circles, and became especially vocal after Tito's death in 1980, when the economic and political situation in Yugoslavia became very strained. Political disputes around economic measures were echoed in the public sentiment, as many Slovenians felt they were being economically exploited, having to sustain an expensive and inefficient federal administration.

Jovanka Broz, Tito, Richard Nixon and Pat Nixon in the White House, 1971

Slovenian Spring, Democracy and Independence

In 1987 a group of intellectuals demanded Slovene independence in the 57th edition of the magazine Nova revija. Demands for democratization and more Slovenian independence were sparked off. A mass democratic movement, coordinated by the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights, pushed the Communists in the direction of democratic reforms.

In September 1989, numerous constitutional amendments were passed to introduce parliamentary democracy to Slovenia. The same year Action North united both the opposition and democratized communist establishment in Slovenia as the first defense action against attacks by Slobodan Milošević's supporters, leading to Slovenian independence. On March 7, 1990, the Slovenian Assembly changed the official name of the state to the "Republic of Slovenia". In April 1990, the first democratic election in Slovenia took place, and the united opposition movement DEMOS led by Jože Pučnik emerged victorious.

The initial revolutionary events in Slovenia pre-dated by almost one year the Revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe, but went largely unnoticed by international observers. On December 23, 1990, more than 88% of the electorate voted for a sovereign and independent Slovenia. On June 25,1991, Slovenia became independent through the passage of appropriate legal documents. On June 27 in the early morning, the Yugoslav People's Army dispatched its forces to prevent further measures for the establishment of a new country, which led to the Ten-Day War. On July 7, the Brijuni Agreement was signed, implementing a truce and a three-month halt of the enforcement of Slovenia's independence. In the end of the month, the last soldiers of the Yugoslav Army left Slovenia.

The Declaration of Independence, June 25, 1991. Photo: UKOM archive

In December 1991, a new constitution was adopted, followed in 1992 by the laws on denationalization and privatization. The members of the European Union recognized Slovenia as an independent state on January 15, 1992, and the United Nations accepted it as a member on May 22, 1992.

Slovenia joined the European Union on May 1, 2004. Slovenia has one Commissioner in the European Commission, and seven Slovene parliamentarians were elected to the European Parliament at elections on June 13, 2004. In 2004 Slovenia also joined NATO. Slovenia subsequently succeeded in meeting the Maastricht criteria and joined the Eurozone (the first transition country to do so) on January 1, 2007. It was the first post-Communist country to hold the Presidency of the Council of the European Union, for the first six months of 2008. On July 21, 2010, it became a member of the OECD.

The disillusionment with domestic socio-economic elites at municipal and national levels was expressed at the 2012-2013 Slovenian protests on a wider scale than in the smaller October 15, 2011 protests. In relation to the leading politicians' response to allegations made by the official Commission for the Prevention of Corruption of the Republic of Slovenia, legal experts expressed the need for changes in the system that would limit political arbitrariness.

National Anthem

"Zdravljica" (written by France Prešeren)

Žive naj vsi narodi

ki hrepene dočakat' dan,

da koder sonce hodi,

prepir iz sveta bo pregnan,

da rojak

prost bo vsak,

ne vrag, le sosed bo mejak!

"A Toast" (translated by Janko Lavrin)

God's blessing on all nations,

Who long and work for that bright day,

When o'er earth's habitations

No war, no strife shall hold its sway

Who long to see

That all men free

No more shall foes, but neighbours be.

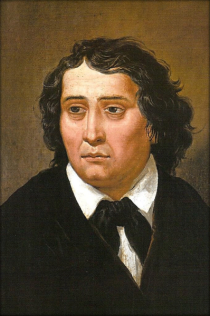

Left: The 1850 oil portrait of Prešeren.

History of the National Anthem

France Prešeren (December 3, 1800 - February 8, 1849) is Slovenia's greatest and most celebrated poet. The national awards for culture bear his name, and are awarded on the National Day of Culture (February 8), an official holiday.

A widely renowned figure of European Romanticism, Prešeren established through his prodigious work a focus for Slovenia's first national program.

Zdravljica (A Toast) represents the peak of Prešeren's political poetry. It was written in autumn 1844, removed from the manuscript of the collection of poems Poezije (1847) by the censors, and published on April 26, 1848 in the newspaper Novice after the collapse of Metternich's absolutism and the termination of censorship. Its dominant idea, a radical demand for freedom of the Slovenian nation, arises from the humanistic vision of equality and friendly coexistence of all nations, and all people's right to independence. It originates from the concepts of the French Revolution of equality, freedom and brotherhood, which were adjusted to the basic political needs of the Slovenian people at the time of the "Spring of Nations" and concerned their independence. However, Prešeren's "Marseillaise" reaches beyond the nature of a political manifesto and bears a strong note of intimate humanity.

In the history of constituting the Slovenian nation Prešeren's Zdravljica was of extreme conceptual significance. It became particularly topical during the occupation and National Liberation Struggle from 1941 to 1945 and in the period of what was called the "Slovenian Spring" in the eighties when it started to be sung as the national anthem on state holidays and major public events.

Zdravljica was proclaimed the new Slovenian anthem on September 27, 1989 when the Slovenian Assembly adopted the Amendments to the Slovenian Constitution. The Law on the National Anthem of the Republic of Slovenia adopted on March 29, 1990 specified the seventh stanza set to the music of Stanko Premrl as the actual anthem.

Following the independence of Slovenia, the National Assembly adopted (in 1994) the law governing the official crest, the national flag and the anthem of the Republic of Slovenia.

When to Visit

September is an excellent month to visit Slovenia because it's the best time for hiking and climbing, and the summer crowds have vanished. A trip to Slovenia in September is always a memorable time as the excitement of the grape harvest and crush adds to the special charm of the people and countryside. December to March is high-time for skiers, while spring is a good time to be in the lowlands and valleys because everything is in blossom. Try to avoid July and August, when hotel rates rise and there are lots more tourists, especially on the coast.

Lake Bled in Autumn